- About Us

- Membership

- What’s On

- ROSL Events

- About Club Events

- Public Affairs

- Calendar of Events

-

Upcoming Events

-

Annual Music Competition, Gold Medal Final 2025

Fri. 18 July - 19:30

![ROSL Annual Music Competition 2024 Wigmore Hall]()

-

NZ Concert & Garden Drinks

Mon. 21 July - 18:15

![ROSL_Pettman_Scholars_2024_Lorna_Madeleine_NZ_Concert]()

-

Saxophone Lounge Nights in the Garden

Fri. 25 July - 18:30

![Brabourne Room & Garden, Club’s Brabourne Room The Garde an Rosl]()

-

Jazz in the Garden

Fri. 01 August - 19:00

![Jazz in the Garden - Oliver Lord]()

-

Jazz in the Garden

Fri. 08 August - 19:00

![ROSL garden Green Park]()

-

Jazz in the Garden

Fri. 15 August - 19:00

![Corporate Photographer London]()

-

Cheese and Wine Tasting with Paxton & Whitfield and Vergelegen Estate

Wed. 20 August - 18:45

![Vergelegen Estate and cheese]()

-

London History Series Talk: The 20th Century and Beyond

Thu. 21 August - 18:00

![20th century London credit alamy stock country life]()

-

Jazz in the Garden

Fri. 22 August - 19:00

![ROSL_garden_green_park_view4]()

-

Jazz in the Garden

Fri. 29 August - 19:00

![jazz-in-the-garden-nights-oliver-lord]()

-

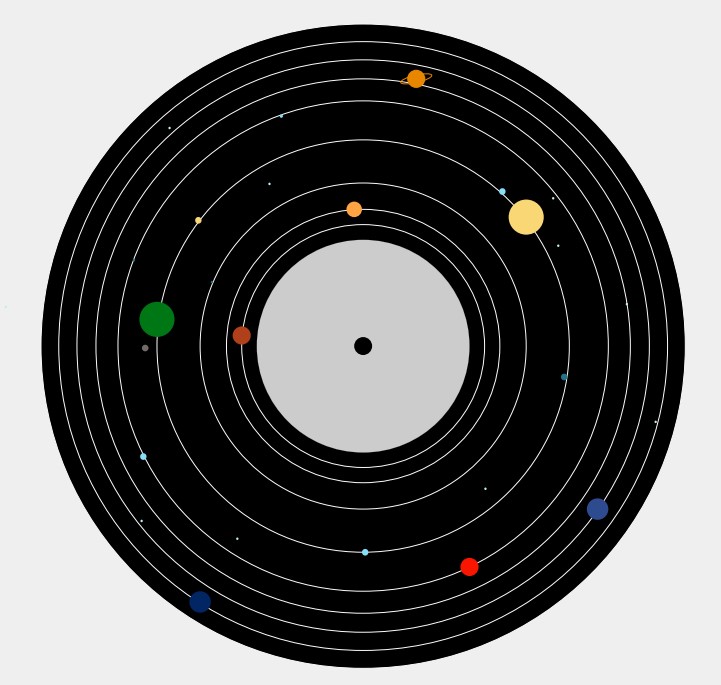

Overseas Journal | Conjuring the Cosmos – The magic behind Holst’s Planet Suite

10 April 2024

As we celebrate Holst’s 150th birthday with a special concert, musician and writer Hugh Morris discovers the inspiration behind the composer’s best-loved works.

A speck appears on the horizon, approaching at speed. Marching forward juggernaut-like is ‘Mars, the Bringer of War’, the first of the seven-movement orchestral piece ‘The Planets’, written by the composer Gustav Holst between 1914 and 1917. In the seven minutes of ‘Mars’, faint becomes blunt, miniscule becomes massive, and terror reigns.

By far his most performed and most popular work, ‘The Planets’ has become the calling card for Holst. But past the fame of ‘I Vow to Thee My Country’ (a setting of part of the ‘Jupiter’ movement, with solemn, patriotic lyrics added by Sir Cecil Spring Rice), the piece also represents something of the man himself. Unlike his colleague and firm friend Ralph Vaughan Williams, Holst struggled with the musical architecture of larger forms – symphonic forms in particular – preferring instead to write smaller musical spans (the chamber opera Sāvitri and the Suites for Military Band are two celebrated examples of that tendency.)

Though one of the longest and most complex pieces he wrote, that sensibility is on show in ‘The Planets’ too. United by a loose programme of titles rather than any sort of musical development or theme, each movement of ‘The Planets’ is remarkably different from one another in terms of tone colour, texture, character and mood. There’s an essential originality to the work too, particularly with the way it is proportioned, with its fearsome opening (‘Mars’) exuberant middle (‘Mercury’, ‘Jupiter’) and its extended inward retreat at the close (‘Neptune’).

Perhaps the main reason that ‘The Planets’ is held so fondly is for its strength as an orchestral canvas. An extravagant statement for large orchestra first performed in full in 1920 – at a time when resources were thin on the ground following the First World War – it requires a big, committed orchestra and a women’s choir to realise this most excitingly colourful of scores. But it was thanks to two dedicated pianists in Hammersmith that it even exists at all.

After graduating from the Royal College of Music and pursuing work as a trombone player in orchestras around the UK, Holst eventually found a job as Director of Music at St Paul’s Girls’ School in Hammersmith. (Holst’s eerie rhapsody for wind band ‘Hammersmith’ is one of a number of pieces that carry references to this time.) Years later, the piano duo (and former staff members at the school) John and Fiona York would uncover a leather-bound score for ‘The Planets’, scored for four-hands piano.

But was it arranged? Or sketched? Or might it have existed for piano beforehand? Unable to properly play the piano due to neuritis in his right hand, Holst enlisted two colleagues, Nora Day and Vally Lasker, as his ‘scribes’. Day and Lasker would play the music of the ailing composer on the school’s Broadwood grand, helping Holst to realise the ideas in his head, while also conducting a lot of the menial work of copying and arrangement. The single piano version of the score – that clocked in at almost an hour of music – was dedicated to them both; without them, what would eventually become the full score would likely never have seen the light of day.

Today, there’s a very literal understanding of the kind of media that might accompany ‘The Planets’: NASA-fied scientific images, underscored by extremely characterful if somewhat eccentric music. But, as Anthony Tommasini wrote in The New York Times in 2010, ‘what the planets might actually be like was not the point’ for Holst. That ‘The Planets’ has little basis in science or space travel is plain to see; in what scientific realm is Jupiter ‘the bringer of jollity’, or Uranus ‘the magician’? Titles like ‘Mercury, the Winged Messenger’ or ‘Neptune, the Mystic’ initially suggest a basis in astrology, but the inspiration for ‘The Planets’ goes further than star charts and horoscopes.

Holst was influenced by the broader aims of the Theosophical movement, which engaged in a re-assessment of cultural values (encouraging areas like spiritualism or mythology) and investigated other, non-European cultures and religions. Holst delved into this world as a way of both broadening his mind (to forms of thought including occultism and gnosticism) and his horizons, especially towards Indian philosophy.

There are traces of all of these philosophical adventures in Holst’s music: ‘Sāvitri’, which sets a section of the Mahābhārata, the gnosticinfluenced ‘Hymn of Jesus’ and ‘The Cloud Messenger’, a setting of Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa. This vein of thought influenced the construction of ‘The Planets’ too. The particular structure of the titles are closely linked to headings in a booklet by Alan Leo that Holst was reading at the time, called What Is a Horoscope? And, while scientifically, the route Holst takes through the solar system makes no logical sense. But, astrologically speaking, ‘the pattern is clear,’ Raymond Head wrote in TEMPO in 1993: ‘The order of the planets symbolis[es] the unfolding experience of life from youth to old age.’ There’s brio, vigour, and melancholy in ‘The Planets’, but something distinctly unusual too. As the score retreats into the distance, some of Holst’s other worlds come into view.

We’ll be holding a special concert to celebrate the birth and works of Holst in 2024; please keep an eye out. View Calendar of Events, and email newsletters for more information.