- About Us

- Membership

- What’s On

- ROSL Events

- About Club Events

- Public Affairs

- Calendar of Events

-

Upcoming Events

-

Strings Section Final 2026

Tue. 03 March - 19:00

![ROSL_Arts_Events__2026_Music_Competition_Strings]()

-

British Pie Week Menu

Wed. 04 March - 12:00

![British Pie Week 2026 lobster]()

-

Commonwealth Day Celebration 2026

Mon. 09 March - 12:00

![Commonwealth]()

-

Commonwealth Menu

Mon. 09 March - 12:00

![commonwealth-menu-2025-1]()

-

String and Keyboard Ensembles Section Final 2026

Tue. 10 March - 19:00

![ROSL_Arts_Events__2026_Music_Competition_String_Ensembles]()

-

Mixed Ensembles Section Final 2026

Tue. 17 March - 19:00

![ROSL_Arts_Events__2026_Music_Competition_Mixed_Ensembles]()

-

Overseas Awards 2026

Tue. 24 March - 19:00

![ROSL_Arts_Events__2026_Music_Competition_Overseas]()

-

Public Affairs Series: Dame Penny Mordaunt

Tue. 31 March - 18:30

![Dame Penny Mordaunt]()

-

Global Expressions of Riesling: A Guided Wine Tasting with Dr Enno Lippold & James Leach

Thu. 16 April - 18:45

![global-expressions-riesling-tasting]()

-

Piano recital with Martin James Bartlett

Fri. 24 April - 18:30

![Martin_James_Bartlett_MMSOL_Arts_Events]()

-

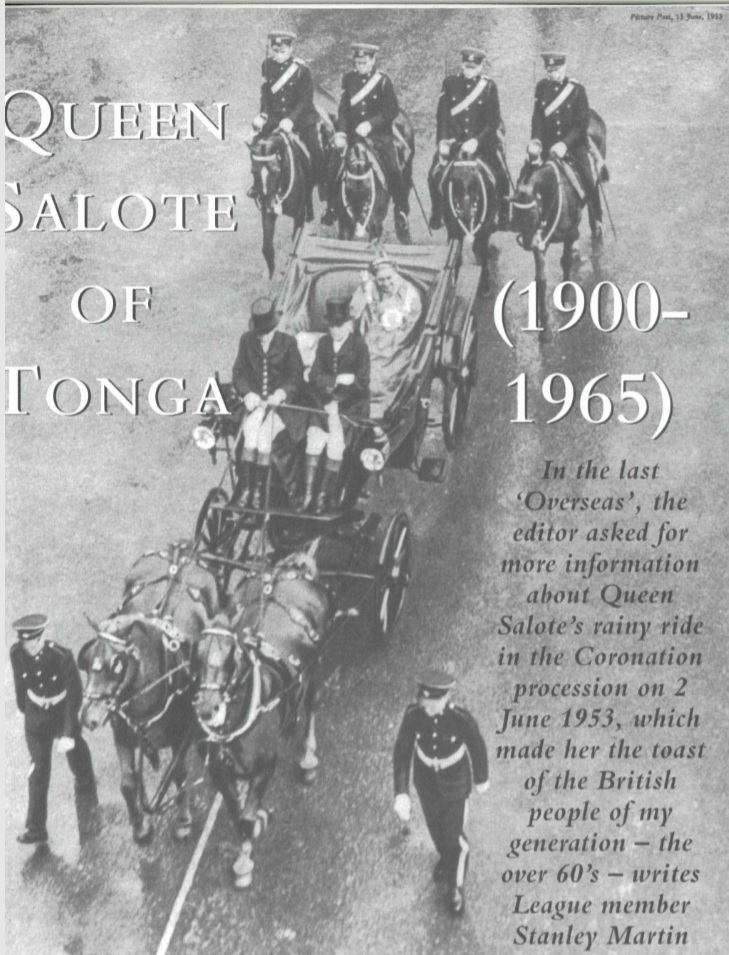

From the Archives: Queen Salote of Tonga

22 February 2018

As a schoolboy, I watched the procession from the front row of the crowd in The Mall, where I had slept overnight, and woke to the news of the ascent of Everest by Hillary and Tenzing. In fact, the procession was made up of several small processions, including that of the ‘Colonial Rulers’; all ‘Highnesses’, except for the ‘Majesty’ of the Queen of Tonga, with an appropriate majestic figure and bearing. She sat in the first carriage, opposite the Sultan of Kelantan. On the way to Westminster Abbey, in the morning, all the carriages were open. On the return from the abbey, in the afternoon, it rained heavily and the only open carriage was that of the queen and the sultan.

Whereas His Highness got very wet, Her Majesty was partly protected by the ample pink silk mantle of a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE), which proved to be an effective raincoat. She had no umbrella, however, and must therefore finished with soaking wet hair.

The press was ecstatic and Queen Salote became a household name overnight. June babies were christened Charlotte (of which Salote is the Polynesian form), a racehorse was named after her and she was the subject of topical songs: “Linger longer, Queen of Tonga”. The Manchester Guardian wrote of “the magnificence of Her Majesty the Queen of Tonga, smiling broadly in a spiteful downpour and heartily waving a powerful bare arm, happy as though all the sun of the friendly islands were beating down”. The Daily Telegraph reported that she received biggest cheers of the day, except for The Queen herself and Sir Winston Churchill and that, later, a woman went up to her car in Knightsbridge and call out “Good luck. You were marvellous”. The Telegraph concluded that “Queen Salote, whose genial dignity matches her proportions, has won an extraordinary quantity of affection from the British people”. The Times described her as “the outstanding overseas figure of the celebrations”.

A story, which has gained currency over the years, is that when, at one of the parties given in buildings overlooking the processional route, someone asked Sir Noel Coward the identity of the small man opposite Queen Salote, the maestro replied: “He is her lunch”.

Queen Salote Tupou III was educated at the Dicesan High School for Girls in Auckland and succeeded her father, King George Tupou III, at the age of 18 – in 1918. In the previous year, she had married her cousin, Prince Uilami (William) Tungi, who served as Prime Minister from 1923 until his death in 1941. In the Second World War, the resources of small Tonga were put at the Allied disposal: three Spitfires were paid for by the Tongan people and a detachment served in the Soloman Islands.

Queen Salote received every honour that the monarch of the United Kingdom could confer on her. She was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 1932 and promoted, in 1945, to be a Dame Grand Cross, thus providing her with that pink mantle that was to be so useful eight years later. When Queen Elizabeth II visited Tonga during her extensive Commonwealth tour towards the end of 1953, she made Queen Salote a Dame Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO). In 1965, the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George was opened to women and, shortly before her death in that year, Queen Salote was made the first Dame Grand Cross (GCMG).

Her death caused great sadness in Tonga, the South Pacific, New Zealand (her second home), and Britain. Diabetes, pleurisy and, finally, cancer had gradually overcome her. It was a sick woman who sat on the veranda of the palace in Nuku’alofa on 30 July 1965 to watch the parade celebrating the longest reign in Tongan history. Her great, great grandfather King George Tupou I, had embraced Christianity before reigning from 1845 to 1893; the ‘Grand Old Man of the Pacific’ died at the age of 96. His great grandson and successor, King George Tupou II (Queen Salote’s father), concluded the Treaty of Friendship and Protection with Britain in 1900, whereby the Friendly Islands (so named by Captain Cook) remained an independent kingdom under British protection.

In early November 1965, Queen Salote, accompanied by her younger son, was flown in an RAF aircraft to Auckland for hospital treatment. A month later, her condition deteriorated and she died on 16 December, an hour before her elder son, because of aircraft delays, was able to reach her bedside.

The funeral took place in Nuku’alofa on 23 December, following a lying-in-state characterised by the special Tongan high ritual of chiefly death: Koe takipo. Fires burned continually throughout the hours of darkness around the palace, with three attendants sitting on three of each burning torch. One attendant held the torch horizontally in the direction the body lay while the other two knocked away the ash to keep the torch burning. For the same period, no food could be prepared inside the palace itself or the grounds and only the new king could eat in the palace, from food cooked outside it. The population of Nuku’alofa was doubled by mourners from the outlying islands, bearing gifts of food, mats and bark cloths for their new ruler. More than 200 men carried the bier from the palace to the royal tombs where the later rites were conducted, according to custom, behind a closed wall of bark cloth screen 150 metres long around the whole tomb. Queen Elizabeth II was represented at the funeral by the Govenor-General of New Zealand and flags flew at half-mast in London on that day.

The links of the Tongan royal family with Britain have been firmly maintained since Queen Salote’s death. Her elder son and sucessor, King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV, is a frequent visitor and was present at Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee Service in St Paul’s Cathedral in June 1977, seated on a large Tudor-style chair originally made for ‘Henry VIII’ in the TV series ‘Elizabeth R’. The always friendly relationship between the Friendly Islands and Britain continues vigourously today but never was better symbolised than by a smiling, wet Queen Salote in 1953.

This story is mentioned, along with the Queen’s visit to Tonga as part of Commonwealth travels, in the March 2018 edition of Overseas.